Update: 19/07/2016

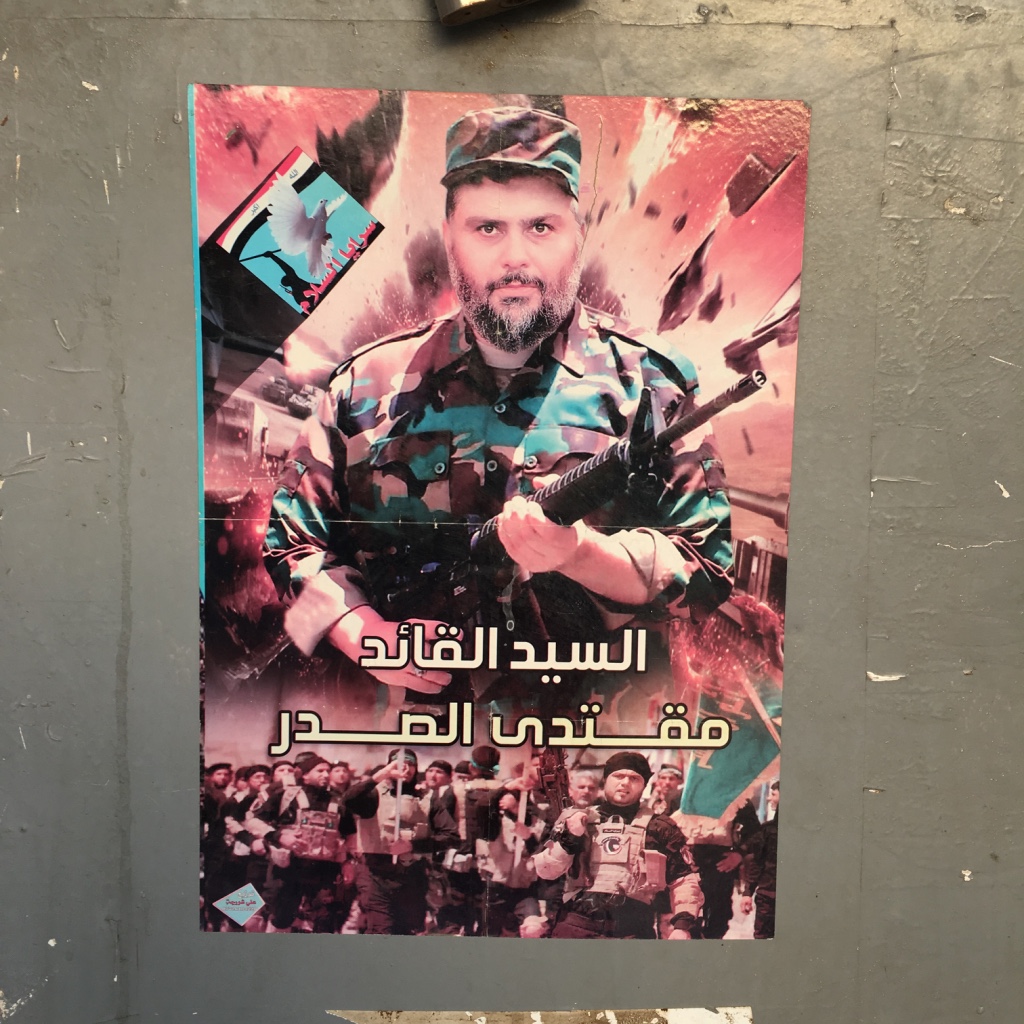

Following from my post providing some analysis of Muqtada al-Sadr’s recent appearance in military garb, @toaf kindly forwarded some fascinating photos he recently took in Iraq. These photos indicate a strategy of integrating a military, nationalist-secular symbology alongside images of Sadr’s religious heritage (Baqir and Sadeq al-Sadr) in campaigns in various parts of Iraq. These photos can be viewed below, followed by the original discussion.

Billboard in Baghdad

Side of tea stall, Baghdad

Merchandise at Kufa

Small town in Dhi Qar Governorate

Al-Mada published an interesting photo of Muqtada al-Sadr wearing a military uniform during a meeting, yesterday, 11th July, with the leaders of the Sadrist ‘Peace Brigades’ (Saraya al-Slaam), the reformed and renamed incarnation of the Mahdi Army. To the best of my knowledge, this is the first time Muqtada has been pictured in military as opposed to religious garb. The picture shows Muqtada, left, and next to him, Abu Duaa al-Issawi the military commander of the ‘Peace Brigades’.

Photo from al-Mada, full story here.

This is the latest example in a trend which has seen Muqtada increasingly move away from religious and sect-based symbols in favour of a more inclusive and secular discourse of nation and citizenship. Or, in other cases, he has sought to reframe religious symbols (e.g. shrines and holy places), redeploying them in his discourse in more inclusive terms as part of a pluralistic national symbology. This trend became particularly pronounced during the period of al-hashd al-shaabi. In part, this phenomenon can be interpreted as a strategy of distinction, Muqtada is seeking to distinguish the Sadrist trend from its most immediate rivals i.e. other Islamist and militia groups that deploy more openly sectarian discourses e.g. Badr, Kata’ib Hezbollah, and Asa’ib Ahl al-Haq. At the same time, Muqtada has sought to align his organisation with the ongoing protests for fundamental political reform that are a major feature in current Iraqi politics. A discourse embracing more secular and nationalist sentiments facilitates this political cooperation. Indeed, this is also borne out by the substance of Muqtada’s discussions as reported by al-Mada in which he reportedly emphasised ‘the necessity of there being no signs or chants which do not celebrate the nation’ during protests against corruption which will take place in Tahrir Square this Friday.

All this indicates an emerging axis of political division in Iraq between, on the one hand, an alliance of civic-nationalist-secular forces combining with an Iraqi-Shi’i Islamist component which is increasingly framing itself through the basic institutions and concepts of the modern nation state; and on the other hand, Shi’i Islamist and militant forces more closely aligned with Iran who continue to resist integration into an Iraqi political field. Both sides of this axis have their sights firmly trained not only on each other, but on the sclerotic Iraqi state, political structures, and reviled political class.

What is perhaps most interesting about Muqtada’s shifting discursive strategy is how it continues to enmesh him in a secularising communicative practice. By this I mean that Muqtada increasingly appeals to forms of legitimacy and authority whose bases are being produced within an Iraqi public sphere and which are framed through its attendant conceptions of legitimate political authority and public interest, as opposed to drawing on the symbolic and legitimating resources that are particular to the Shi’i religious field. Consequently, Muqtada is increasingly called upon to define and defend his actions in the terms of this Iraqi public sphere, a fact which structures his potential strategies of political action in a way that simply doesn’t apply to other political and militia organisations associated with the hashd and which receive Iranian patronage. It is true that Muqtada continues to draw on forms of social power from the religious field. But his own social and political practice increasingly alienates him from these resources. That Muqtada can continue to exploit religious forms of authority and legitimation is thanks, in part, to others, such as Ali al-Sistani, whose social practice continues to reproduce the Iraqi-Shi’i religious field as a relatively autonomous social field, unintegrated into the political field, and constructed around ‘sacred capital’, or the dissemination of what Weber termed ‘the goods of salvation.’

1 reply »